Elephants at Work

Elephants at WorkFrom a photograph copyrighted by the Keystone View Co.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Wonders of the Jungle, Book Two, by Prince Sarath Ghosh This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Wonders of the Jungle, Book Two Author: Prince Sarath Ghosh Release Date: December 9, 2008 [EBook #27463] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WONDERS OF THE JUNGLE, BOOK TWO *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Carla Foust, Joseph Cooper and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Printer errors have been changed, and they are indicated with a mouse-hover and listed at the end of this book. The author's spelling has been maintained.

Elephants at Work

Elephants at WorkHEATH SUPPLEMENTARY READERS

PRINCE SARATH GHOSH

Book Two

D. C. HEATH AND COMPANY

| BOSTON | NEW YORK | CHICAGO | ATLANTA |

| DALLAS | SAN FRANCISCO | LONDON |

Copyright, 1918,

By D. C. Heath & Co.

3 B 1

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

My dear, I am now going to tell you many more Wonders of the Jungle, as I promised to do in Book I.

In that Book, as you will remember, I promised to tell you more about the elephants and about the laws of their herd. So I shall do so now.

Then I shall tell you about some animals which I did not describe in Book I. Among these you may like to know especially about the tiger, the lion, the leopard, and the wolf.

You may like to know how really clever some of these animals are, and how some of them have affections, just as we have.

But while you are reading about them, you must try to think. Then you will understand why these animals do certain things. And that will show how clever you are!

I have used a few new words in this Book. But I am sure you know them already.

Now I shall begin with the laws of the elephants.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Elephant Herd a Republic | 1 |

| The Duties of the President | 2 | |

| He Must Provide Daily Food | 3 | |

| He Must Provide Daily Drink | 9 | |

| He Must Keep Order in the Herd | 12 | |

| He Must Avoid Danger from Outside | 18 | |

| II. | War and Neutrality in the Jungle | 26 |

| Wise Elephant Leader Avoids War | 27 | |

| Wise Elephant Leader Keeps Neutral | 29 | |

| When it is Impossible to Remain Neutral | 29 | |

| III. | The Policemen of the Elephant Herd | 31 |

| IV. | The Punishment of the Wicked Elephant | 39 |

| The Princes and the Bad Elephant | 40 | |

| The Trial of the Criminal Elephant—as in a Court of Law | 55 | |

| The Infliction of the Punishment | 57 | |

| The Rogue Elephant | 61 | |

| The Brand of the Rogue | 63 | |

| The Reward of Repentance | 64 | |

| V. | Flesh-eating Animals: The Felines, or the Cat Tribe | 66 |

| The Feline has Strong Fangs | 67 | |

| The Feline's Tongue is Rough | 68 | |

| The Feline's Claws are Retractile | 68 | |

| The Feline has Padded Paws | 71 | |

| VI. | The Tiger[vi] | 73 |

| The Life History of the Tiger Family | 78 | |

| The Tiger's Family Dinner | 83 | |

| VII. | The Tiger Cubs' Lessons | 87 |

| Tiger Cubs Learn to Kill Prey, After their Parents have Caught It | 88 | |

| Tiger Cubs Take Part in Hunt to Catch Prey | 90 | |

| Tiger Cubs Learn to Catch Prey by Themselves | 91 | |

| VIII. | The Tigress Mother's Special Duties | 97 |

| The Truce of the Water Hole | 100 | |

| IX. | The Special Qualities of Tiger and Tigress | 102 |

| Both Tiger and Tigress Defend Their Cubs | 104 | |

| The Tiger Family's Lost Dinner | 110 | |

| The Tiger as a Heroic Husband | 116 | |

| X. | The Lion | 128 |

| The Lion Has the Fangs, the Tongue, the Claws, and the Paws of a Cat | 132 | |

| How the Lion is Different from Other Cats | 138 | |

| XI. | The Lion's Daily Life | 142 |

| XII. | The Lion a Noble Animal | 156 |

| Androcles and the Lion | 156 | |

| The Lady and the Lioness | 163 | |

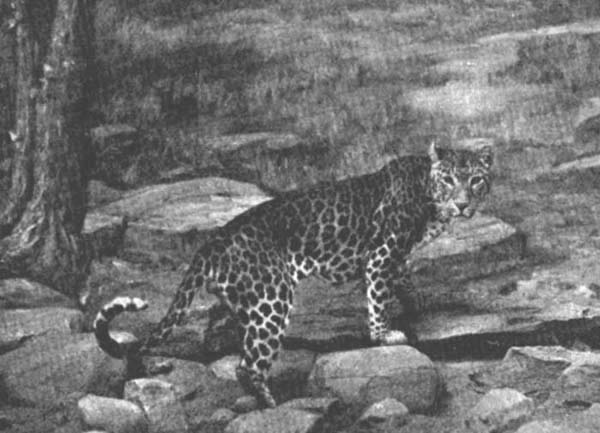

| XIII. | The Leopard | 168 |

| The Leopard's Ground Color and Spots | 169 | |

| Why the Leopard has Spots | 170 | |

| XIV. | The Leopard's Habits | 176 |

| The Panther: Popular Name For Large Leopard | 180 | |

| How the Leopard Seizes his Prey[vii] | 181 | |

| The Leopard's One Amiable Quality—He Loves Perfumes | 182 | |

| The Leopard and the Lavender | 183 | |

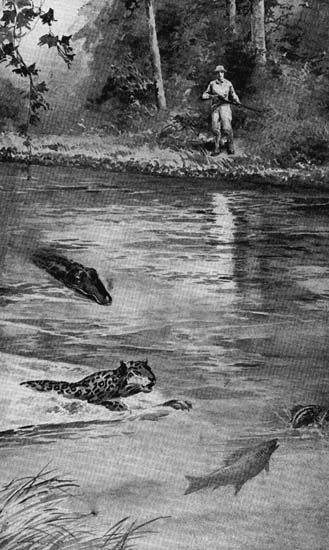

| XV. | American Leopard: The Jaguar | 188 |

| XVI. | The Dog Tribe | 194 |

| The American Gray Wolf | 196 | |

| The American Wolf Learns to Evade the Gun | 200 | |

| The American Wolf Learns to Evade the Trap | 202 | |

| The American Wolf Learns to Evade the Poison | 205 | |

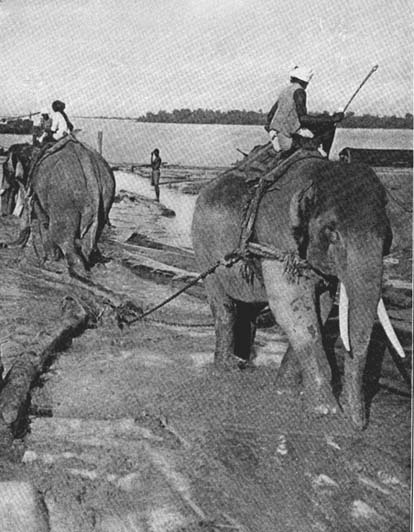

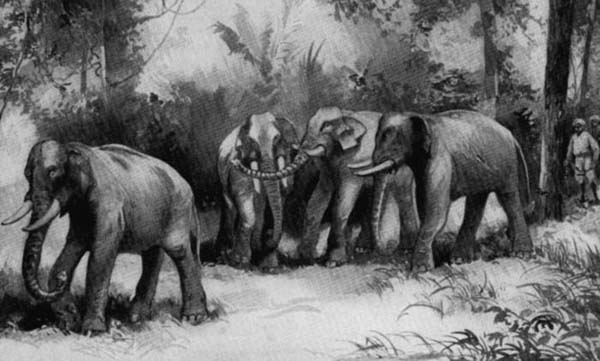

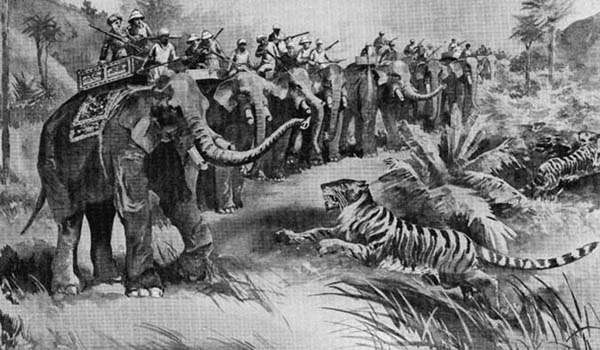

| Elephants at Work | Frontispiece | |

| PAGE | ||

| Elephant Leading Herd Through the Jungle | 5 | |

| Trained Elephants at the Court of a King | 23 | |

| Elephants Guarding a Bad Elephant | 33 | |

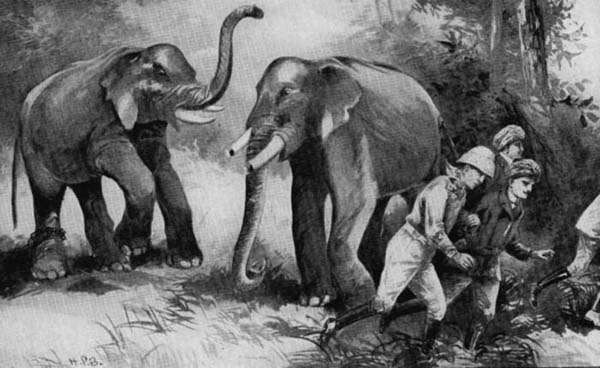

| Policemen Elephants Arresting a Criminal Elephant | 45 | |

| Good Elephant Heading off a Criminal Elephant | 51 | |

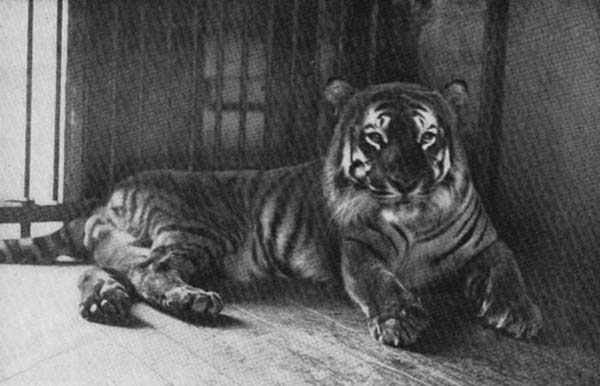

| Tiger | 75 | |

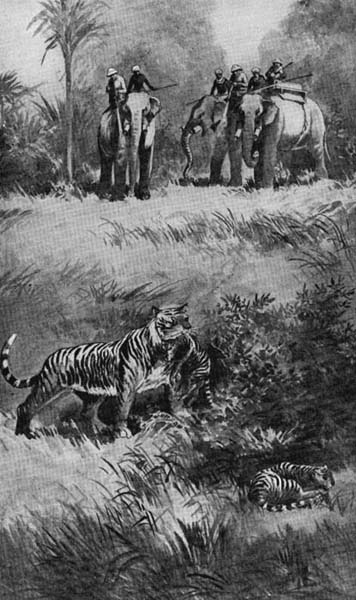

| Tiger Protecting his Cub | 107 | |

| Tiger Charging Hunting Party | 121 | |

| Group of Lions | 129 | |

| Puma | 129 | |

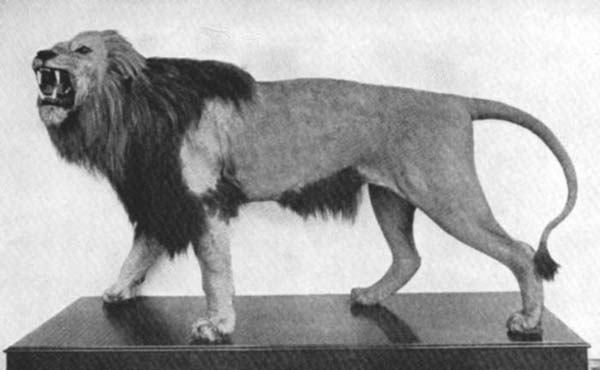

| African Lion | 133 | |

| Giraffes | 147 | |

| Kangaroo | 147 | |

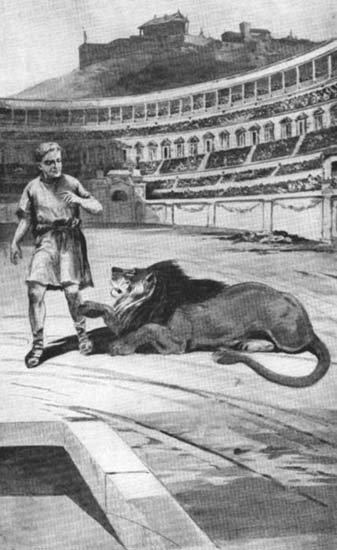

| Androcles and the Lion | 161 | |

| Leopard | 171 | |

| Jaguar | 171 | |

| The Chain of Conflict in the Jungle | 191 | |

| Gray Wolf | 197 | |

An elephant herd is a kind of republic, something like the United States of America, only much smaller and much simpler. So its leader is a sort of president. He is usually the wisest elephant in the herd.

You may like to know how the elephants choose their president. I shall tell you how they do that.

But you must first consider how the people of the United States choose their President. They find out who among their important men is best able to lead them in all the great duties of the nation. Then they choose him.

But if afterward they find that he is not leading the nation in the wisest manner, then the people of the United States choose another man to be their President the next time.[2]

The elephants in a herd do something like that. They first follow the elephant who, they think, is best able to lead them. But if afterward they find that he is not leading them through the jungle in the right way, and that another elephant could lead them in a better manner, then they follow him instead. He then becomes the president of the herd.

"But what is the best way of leading the herd through the jungle?" you may ask.

I shall now tell you about that. The best way to lead the herd is to satisfy all their needs. So the president of the herd has four great duties.

First Duty: He must lead the herd in such a manner that all the elephants will get enough food to eat every day.

Second Duty: He must lead the herd in such a manner that all the elephants will get enough water to drink every day.

Third Duty: He must keep order in the herd, and not allow any naughty elephant to fight or quarrel.

Fourth Duty: He must guide the elephants in such a manner as to avoid all danger from outside;[3] and if such danger does happen to come, he must guard the herd from that danger.

I shall now tell you about these four duties more fully.

Elephants are such large animals that they need a great amount of food. So they have to walk a long way every day, munching the leaves of the trees as they go.

They walk in line, one behind another, as that is the easiest method of walking through the thick jungle; for then one gap through the jungle is enough for all the elephants to go through, one at a time, and they need not make a different gap for each elephant.

Now you will understand that if that one gap is big enough for the largest elephant to go through, it is of course big enough for all the elephants to go through. So, if the largest elephant walks first, in front of the line of elephants, he can force a way through the thick jungle that will be big enough for all the other elephants who come behind him.

So usually the largest and strongest bull elephant is the leader of the herd—if he also[4] has the other qualities of a president, which I shall presently describe more fully. To have all the qualities of a president, he must not only be strong, but also wise and clever. Why? Because even in merely going through the jungle a wise leader avoids many difficulties. It might be that the jungle straight ahead was very thick, and it would be hard to force a way through it; but by turning a little to the right or to the left, an easier passage could be made. This a wise leader would find out, and then turn in that direction.

Again, in the jungle, the ground is sometimes too soft; it might be made of clay which had become soft owing to rain a few days before. But elephants are such heavy animals that they cannot go far over soft ground, as their feet would sink in too deep. And the ground might be covered with bushes or tall grass, so that the elephants could not see to what distance the ground was soft. They might not mind going over soft ground for a few yards, but they would not like to go over such ground for a whole mile.

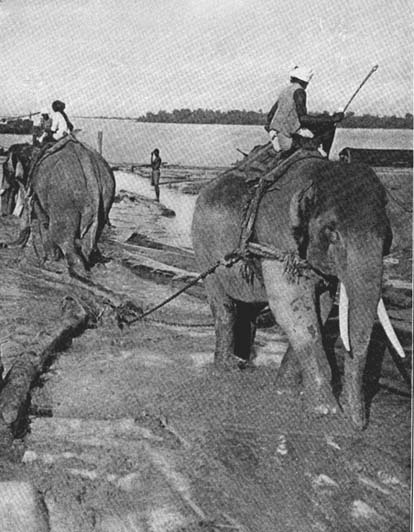

Elephant Leading Herd through the Jungle

Elephant Leading Herd through the Jungle

So a wise leader would know by glancing around how far the ground was likely to be soft; and if he learned that it was likely to be[7] soft for a large area, he would turn at once and go around it. But a foolish leader might take the herd right into the soft ground, and they would all be stuck in the mud, and have a lot of trouble getting out of it again.

So if the herd has chosen merely the biggest and strongest elephant to be their president and he makes such mistakes as that, they soon depose him; that is, they no longer follow him. They look around for some other leader who can discover a better way, and they follow him instead. And if afterward they find that he is wise and clever, and does not make mistakes, they follow him as their leader every day after that, even if he is not quite so big and strong as the other elephant was.

He then becomes the new president, if he is at least strong enough to make a good gap through the jungle. Most of the elephants could pass through that; only the biggest bull, the deposed president, would have the trouble of enlarging the gap with his body in going through it. And this would serve him right!

In the same manner the leader of the herd must not go over ground that is too hard, for elephants are such heavy animals that it jars the bones of their feet to go over hard ground[8] for a great distance. If there has been no rain for several weeks, then in a hot country the ground gets very hard in some places. So if there has been no rain near a herd for some time, a wise leader avoids these hard places.

So, as you see, an elephant leader has to be quite clever in merely avoiding difficulties, in the daily search for food. And that is not all! The food itself may be plentiful in one part of the jungle, and rather scarce in another; for in one direction there may have been just enough showers recently to bring out the fresh leaves on the trees; but in another direction there may have been no rain at all for some time, and so there would be no fresh leaves there.

Why, even in your own town there may be a good shower of rain in one part of the town, and no rain at all in another part. So it might be in the jungle; a wise leader would know this by instinct, and he would take the herd along that part of the jungle where there had been recent showers of rain, and where there would be enough fresh leaves.[9]

After the elephants have had enough to eat for the day, they must have enough clear water to drink. And to get this is the hardest daily duty of the leader.

In the jungle, even if the leader makes a little mistake and goes the wrong way, there may still be enough to eat, because the elephants can always find enough trees in the end by going a little farther: so they would have only a little more trouble in getting their food, if the leader made a mistake. But with water it is quite different—the leader may find no water at all, if he makes a mistake and leads the herd the wrong way.

"Then how must he lead the herd so as to find water, as well as food?" you may ask.

I shall tell you. In most jungles there is a river or even a small stream from which the elephants can drink. But the river or stream may go winding in and out of the jungle, so that it is in one part of the jungle but not in another part. So a wise leader tries to keep his herd near one of those parts of the jungle through which the river flows.

In fact, if the elephants and even the other[10] wild animals are lucky enough to find a fairly big river, and the jungle near that river has plenty of food in it, then the animals stay near there almost all the time. They eat from the jungle and drink from the river; and sometimes they come to the very same place to drink—as at the Midnight Pool, which I described to you in Book I.

So if the leader of the elephant herd is lucky enough to find such a jungle, with plenty of food and a big river in it, he keeps the herd there all the time; and then they have no more trouble about food or drink.

But suppose the leader cannot find such a place? Suppose there is a river, but not enough food near the river? Then what does a wise leader do?

He leads the herd in such a way as to make a kind of curve. He goes into the jungle by the easiest way in the beginning; then, after the elephants have eaten a little, he starts turning slightly toward the direction in which the river flows. When the elephants have eaten a little more, he turns still more in that direction.

In this manner he leads the herd in a kind of curve toward the river, browsing all the way from the trees near by. So, at the end of the[11] day, when the elephants have had enough to eat, they reach the river and have also enough to drink. Is not that a very clever method of providing both food and drink for the herd?

If the herd sleep near the bank that night, they start from there the next morning in their search for food; and they usually go into the jungle by the same path by which they came. But on returning to the river to drink that night, the leader need not bring them back by exactly the same path.

The fact that they did not have enough to eat right near the river shows that the jungle is not very thick there; so the elephants will have no trouble in making a fresh path, a little higher up the river, or a little lower down. A wise leader usually does that: he leads the herd to the river slightly higher up or lower down, and so he makes a slightly different curve through the jungle. Why? Because if he kept to exactly the same curve from the jungle to the river every day, the herd would eat up all the leaves along that path in a few days. So, by changing the curve a little from time to time, he allows fresh leaves to grow there meanwhile.

You now understand why the president of[12] the elephant herd must be wise and clever to do all that I have told you so far. Even among men the President of a Republic has similar duties to attend to, though in a different manner: he too has to govern his country in such a manner as to provide the people with their daily wants, if they obey the laws and do honest labor.

In the elephant herd everyone has to do honest work, as he has to gather his own food; and he has also to obey the laws of the herd. I shall now tell you about that.

The third duty of the elephant leader is to keep order in the herd. Most elephants are by nature gentle, docile, and obedient. That is why men can tame them and make them work; otherwise, if elephants were by nature fierce and disobedient, men could not train them so perfectly as to perform at a circus, or carry people in a procession. So even in the jungle, where the elephants are wild, they usually obey the leader and keep the laws of the herd.

These laws chiefly concern their daily food and drink. As I have told you, in their daily search for food the elephants march in a line,[13] one behind another. A selfish elephant in the middle of the line might want to stop and eat up all the leaves on a tree near him; and if he did so, he would block the way for those behind him, and besides, there would be no leaves on that tree for them to eat when they came to it.

So there is a general rule in the herd that each elephant must take just a few of the leaves from a tree, and then move on; and if instead he does block the way, the elephants behind him may push him forward and make him move on.

"But," you may ask, "why can't the other elephants behind him also stop and eat up all the leaves on the trees near them?"

Because then all the trees on that line of march would be bare of leaves, and it might take a whole month for fresh leaves to grow there again. But if the herd took only a portion of the leaves from each tree, there would be enough food for them along that path if they happened to visit it again in a few days.

In fact, the elephants need make only a few such paths through the jungle, if they eat only part of the leaves at a time along any of the[14] paths. Then they can visit these paths in turn on other days, and always find enough food there—because the fresh leaves constantly growing on the trees would make up for the small portion they had eaten.

So you understand how wise the elephants are in having that law in the herd.

"But," you may say, "if they were to eat all the leaves on a tree, their path would be a short one; while if they eat only a portion of the leaves, their path would be much longer, as they must nibble from many more trees to satisfy their hunger."

That is quite true. But there is no advantage in having a short path, because at the end of their march in search of food they must find water to drink, as I have already told you—and they may have to go several miles to reach the nearest stream. So they might as well nibble from the trees all the way to the stream, especially as elephants can easily march ten or twelve miles in that manner every day.

Besides, after taking a bunch of leaves from a tree, they must chew it before taking the next bite; so, meanwhile, they might just as well walk on to the next tree. In fact, if they[15] have not quite finished chewing, most elephants pass by one or two trees before taking the next bite. That shows how really wise they are. For then they are sure of finding enough food along that path when they visit it again a few days later.

It is the president of the herd who sets a good example to the others in doing all these wise things. As he walks at the head of the line, he sees at a glance what is the best thing to do in that particular path, whether to nibble a little from every tree, or to pass by a few trees without nibbling from them at all. And whatever he does, all the other elephants do after him.

My dear children, it is exactly the same among us. When food is scarce in a country and people must be careful, then it is the President who tells us how to portion out the food supply in the country. Otherwise, some people would be wasteful and throw food away—and others would not have enough to eat.

It is very important to learn from your childhood to be careful of food. Do you know that in the United States every man, woman, and child on an average throws away every year seven dollars' worth of food on the plate?[16] That would be enough to feed all the people in the poorhouses and the hospitals.

Elephants are most careful of their food. Their president is all the time thinking of the best method of making the food supply of the jungle last them from season to season. But the other elephants must help him to do that, by following his good example. If any particular elephant is selfish and wants to eat up at once all the food near him, he is pushed out of the line by the other elephants, as I have already told you. If he is naughty again, he is more severely punished.

How he is punished, I shall tell you in another chapter. I shall then tell you how all sorts of naughty elephants are punished; for, just like people in a country, I am sorry to say that there are in the jungle a few elephants that do not obey the law.

An elephant can be selfish not only in eating, but also in drinking. You will remember what I told you in Book I—how all the elephants stand in a line along the bank of a stream and drink; and after they have all satisfied their thirst, they may jump into the water to bathe and swim.

It would be very selfish for an elephant to[17] jump into the water before the others had finished drinking; for then he would muddy the water which some of the others were still drinking. And for such conduct an elephant is very severely punished.

But the very worst offense in an elephant herd is quarrelling and fighting; for, sometimes, two elephants do quarrel and fight, just like a couple of naughty boys in school. But there is never any real need to quarrel in an elephant herd; for if one of the elephants has done wrong or broken the rules of the herd, he will be punished by the president of the herd—just as in school a naughty boy would be punished by the teacher or by the head of the school.

It is not necessary for any other elephant in the herd to quarrel or fight with the naughty elephant, even if he has been injured by him; the president of the herd will punish the naughty elephant soon enough. So if two elephants do fight, both of them are punished; of course the one who began the fight is punished more severely than the other.[18]

The president of the herd must lead the elephants in such a manner as to avoid any danger that may come to the herd from outside. In the jungle there are other wild animals; most of them are, of course, too small to be able to hurt so large an animal as an elephant; but a tiger is so strong and so fierce that he could kill a small, half-grown elephant.

The tiger could hide in the jungle, and if the small elephant happened to stray from the herd, the tiger could spring upon it and kill it. So the president of the herd usually keeps the elephants away from any part of the jungle which he knows to be infested by tigers.

How does he know that? By the paw marks made on the ground by the tigers. For the tigers leave plenty of paw marks on the ground in coming in and out of their dens to hunt their prey every day. So if the president of the elephant herd comes across a line of such paw marks, he turns aside and leads the herd in another direction.

Of course, if the herd happened to meet a tiger quite suddenly, they would at once face the tiger. And the tiger would never dare to[19] attack even the smallest elephant if the big ones were near, for they could drive him off with their tusks or trample upon him.

But the greatest danger that can come to an elephant herd from outside is from men. Men sometimes go into the jungle to shoot wild elephants with guns, or to catch them alive in huge traps. So the leader of the herd must find out where the traps are, or where the hunters are hiding; and then he must avoid such places.

You will remember what I told you about Salar and his father in Book I. Salar was the boy elephant who nearly fell into a most tricky trap, but his wise old father suspected the trap and called to Salar to halt; and because Salar obeyed his father and halted at once, he just escaped falling into that awful trap.

Well, in the jungle hunters lay all kinds of traps to catch wild elephants alive; and sometimes for several years the hunters try over and over again to catch the elephants, if they fail to catch them at once. So the president of an elephant herd has to look out for traps all the time; and the herd that has the wisest president escapes capture for the longest time.[20]

In fact, as Salar is an actual elephant, not an imaginary one, I may tell you that his father was such a wily leader of his herd that he kept them from capture for ten years longer than the leader of any other elephant herd in that jungle.

As for hunters who seek to kill wild elephants with guns, the leader of the herd has to be even more careful in avoiding them. These hunters usually hide behind bushes, and try to creep up to the elephants; and when they are within a hundred yards of the elephants, they begin shooting them. Then the leader of the herd has to prove his wisdom.

A foolish leader would stand still, or even try to charge the hunters; and then more of the elephants would get killed. But a wise leader gives the signal to run away as soon as he hears the sound of the first gun; then at most only one or two of the elephants are killed—and sometimes none at all.

Why? Because to kill an elephant with a gun a hunter must hit him exactly in one particular place on the body—behind the elephant's ear, where the skin is thin. At the first shot the hunter may not hit the elephant just there, but inflict only a trifling wound[21] elsewhere on his thick skin. So by running away at once an elephant may save his life.

But as all leaders are not so wise, the hunters usually manage to kill one or two of the elephants. I may tell you that these hunters kill the elephants merely to get their tusks, which they sell as ivory.

It is a shame to kill such wonderful animals just for money; and you ought to know that in some parts of Africa almost all the elephants have now been killed. If the hunters continue to do that, there will be no elephants left in Africa in a few years. Then the hunters will not be able to get the very ivory for the sake of which they now kill the elephants.

But you will be pleased to know that in India and other countries of Asia nobody is allowed to kill a wild elephant; for if anyone did so, he would be put into jail. Special hunters are allowed to catch wild elephants alive, as I have already told you; and then the elephants are tamed and trained to do all kinds of useful work, such as to pile logs, build bridges, make roads, and lay water-pipes (see Frontispiece). Some of these elephants are also taught to do tricks in a circus, or to carry grand people in a procession.[22]

"Then how do people in India get their ivory, if they never kill an elephant?" you may ask.

They get the ivory when the elephant dies naturally; and the ivory is just as good then as before. Is not that very wise? The people of India first get the help of the elephants in doing all their heavy work, and at last they get the ivory also.

There are huge buildings in India, some of which are more than two thousand years old, which are so wonderful that engineers in America and Europe do not know exactly how those buildings were erected. There is a particular temple on the top of a mountain; and that mountain is 6000 feet high. The ceiling over the center of the temple is a huge circular piece of marble; and that marble ceiling is so large that for a long time people in America and Europe did not know how it was dragged up to the top of the mountain, and then placed over the temple. But now we know that a team of trained elephants was used to do that.

Trained Elephants at the Court of a King

Trained Elephants at the Court of a King

You will be pleased to know, too, that the people who built that temple are called Jains, whom I mentioned in Book I, page 163 (footnote), as the people who are kind to all animals,[25] and who never hurt even the smallest insect. Instead, these mild and gentle people have taught dumb animals to help them build one of the greatest wonders of the world.

How the elephants were taught to do that, I shall tell you in the next Book.

Now I must tell you about another duty of the president of the elephant herd: he must avoid another kind of danger that may come to the herd from outside.

I am sorry to say that herds of elephants sometimes fight with one another, just as nations of people do. Alas, although elephants are usually such wise animals, they are sometimes as foolish as men! Two herds of elephants may find the same feeding ground, which has plenty of trees to eat from, and a convenient stream of water to drink from. Then the two herds may start fighting for that new feeding ground—just as two nations sometimes fight for a new land.

Among elephants the herd that first finds the feeding ground usually keeps it; but another herd may come there at about the same time, and claim to have found it first—and may fight the other herd for that new feeding ground. Or it may happen that the second herd really[27] came there later, but is stronger than the first herd, as it has more bull elephants in it. Then the second herd may try to drive away the other herd, which really found that feeding ground first.

Then what does the president of the first herd do? Alas, he usually stays there to fight it out. But he gains nothing by it; instead, some of his bulls get killed or wounded—and in the end his herd has to flee just the same. A very wise leader would have done that from the first; for he might find another feeding ground just as good somewhere near. And besides, the quarrelsome herd will be punished soon enough!

"How will it be punished?" you may ask.

I shall tell you. A quarrelsome herd gets into the habit of quarrelling with other herds, just as a quarrelsome boy gets into the habit of quarrelling with everybody—or even as a quarrelsome military nation gets into the habit of quarrelling with other nations. Then that quarrelsome boy might meet a stronger boy some day—and get a good thrashing! And the quarrelsome nation might attack a more[28] powerful nation some day—and get a good thrashing!

So also that quarrelsome herd of elephants might some day attack a herd which proves to be stronger. Then that naughty herd would also get a good thrashing. So it is foolish, indeed, for the president of a herd to domineer over weaker herds in the jungle.

Indeed, there is a still greater punishment for a quarrelsome herd. I have already told you that there are hunters who lay traps to catch wild elephants alive. Well, these hunters try specially to catch a quarrelsome herd first! Why? Because quarrelsome herds kill or injure other wild elephants with whom they fight. But the hunters do not want to have any of the elephants killed or injured, as they want to catch as many of them as possible in order to teach them to do useful work. So they catch the quarrelsome herd first, before it can kill or injure many of the other elephants.

Of course, the hunters know which is a quarrelsome herd, because they send men into the jungle from time to time to watch different herds and keep track of them.[29]

There is still another duty that the leader of the elephant herd must do. Sometimes it happens that as he is taking his herd through the jungle, he meets two other herds that are fighting. Then what must he do?

He must lead his herd by another path. He must not take part in the fighting between the two other herds. He must keep neutral.

What does that mean? It means that he must not meddle with other peoples' fights and quarrels. He must not take sides; that is, he must not help either of the herds to beat the other. That is the usual rule in the jungle which a wise elephant leader tries to keep.

But there is an exception to that rule. It sometimes happens that it is impossible for the president of an elephant herd not to take sides. When does that happen? I shall tell you.

When two herds are fighting, they may get very reckless. When men make war, they knock down houses with their guns, and trample on growing corn. In the same manner, when two herds of elephants fight they knock[30] down trees, and trample on shrubs and bushes—sometimes the very trees and shrubs and bushes for which they are fighting! There never is a fight of any kind without a lot of damage being done.

So it may happen that one of the fighting herds gets so reckless that it comes into the ground of the herd that has kept neutral, and does a lot of damage there. Then what must the president of the neutral herd do? He must defend his own ground from damage.

So long as the fighting herds kept to their grounds, he must not interfere. But when one of the fighting herds comes into his ground and does damage, he must defend his rights. A wise elephant leader always does that; for he has bull elephants of his own who can drive out the intruders.

I have already told you that the president of an elephant herd must keep order within his own herd; that is, he must not allow a naughty elephant to commit a crime, such as to attack any other member of the herd. And if a naughty elephant does commit a crime, it is the duty of the president to punish him.

I shall now tell you how he does these things. There is a wonderful police system in an elephant herd.

You will understand that better if I tell you first about an old police system among men. You will read in history books about the Anglo-Saxons, who were the forefathers of most of the people of England and of the United States of to-day. These Anglo-Saxons had a police system like this:—

In a village or in a town all the grown-up men were divided into groups of ten men; and if any man tried to commit a crime, all the other nine men of his group tried to prevent him. If he committed the crime before the other[32] nine men could prevent him, they at least arrested him. Then they took him before the judge for punishment.

It is something like that in an elephant herd in the jungle; only, as there are not so many bull elephants in a herd as there are men in a village, it is not necessary to divide the bulls into different groups.

As there are only twenty or thirty grown-up bulls in an average elephant herd, it is the duty of all the grown-up bulls to prevent a bad elephant among them from committing a crime; and usually it is the bulls nearest to him who actually stop him from committing the crime. If he manages to commit the crime before they can prevent him, they surround him immediately and keep him there like a prisoner, till the president of the herd comes to punish him.

My dear children, that is a great lesson for us. A good citizen always helps to keep the law; if he sees anyone breaking the law, he tries to prevent him from doing so. Some men do nothing, if they see a person breaking the law; they say, "It is no business of ours." Elephants are much better citizens of the jungle in that respect; they always try to prevent a bad elephant from breaking the law.

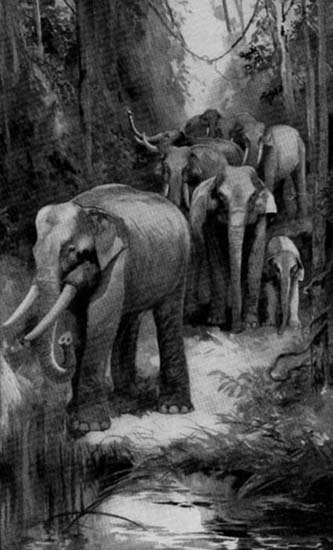

Elephants Guarding a Bad Elephant

Elephants Guarding a Bad Elephant

[35]Now I am going to tell you something that will astonish you—as it has astonished a good many clever scientific men. Do you know why people are at all able to use elephants in a circus, and give you pleasure by making them do tricks? Suppose one of the elephants suddenly went mad? Then he could kill a dozen people in a minute by just rushing at them and trampling on them. No men could stop him, even if they had guns ready all the time; for it might take several minutes to kill an elephant even with a special kind of gun. And meanwhile the mad elephant could trample upon scores of people in a crowded circus.

And it is just the same in a procession, when elephants are used to carry grand people—kings and queens, princes and princesses, lords and ladies. An elephant in a sudden fit of rage could kill many of them.

Then why do people use elephants in a circus or in a procession? Why do they trust themselves with such large and strong animals? Just think!

"Because an elephant is naturally docile and gentle," you may say.

That is quite true. But still a bull elephant might get into a sudden fit of rage about some[36]thing, just like a naughty boy; and as a naughty boy in a sudden fit of rage might break things, so also that bull elephant might rush about and trample on people.

Then why do people trust themselves with elephants? Think again!

It is because of the police system among the elephants themselves. Because if any elephant in a circus or a procession tried to do any mischief, even in a sudden fit of temper, all the other elephants there would prevent him! The men there might not be able to prevent him; but the other elephants could, and they would.

Nobody need tell the other elephants to do that. Without being told to do so, they would rush to him, surround him, and prevent him from doing any mischief. And if only one bull elephant happened to be near enough to him at that time, he would at least head him off—that is, throw himself in the way of the angry elephant. I shall tell you a wonderful story about that presently.

I have said that nobody need tell the other elephants to prevent a bad elephant from committing a crime. The other elephants would do that themselves, because they have got into the habit of doing so in the jungle.[37]

I must tell you that almost all the elephants you see in a zoo or a circus were once wild in the jungle; they have been caught, then tamed, then trained. But they still remember the laws of the jungle; and they follow those laws whenever necessary—just as children who get into the habit of keeping the rules of their school also form the habit of keeping the law when they grow up. So the men who use elephants allow them to practice this particular law; that is, they allow and encourage the elephants to continue this police system among themselves.

From this you will understand that people do not usually use a bull elephant singly; that is, they usually use a number of bull elephants together, so that all the others would prevent a bad elephant from doing any sudden mischief.

Wise people who know the habits of elephants usually use a number of them at a time. But there have been many foolish people who have used a bull elephant by himself; then somebody has ill-treated that elephant, and in his rage he has done a lot of harm.

That actually happened in a big zoo recently. Then they had to shoot the elephant. That shows that the people at that zoo knew very[38] little about the habits of elephants. They should have kept that elephant with a few other elephants.

You may like to know how wise people in Europe and America have learned the habits of elephants. They learned them from the people of India many centuries ago. The people of India first observed wild elephants in the jungle; and they discovered that the elephants had wonderful laws in their herds—which I have described to you. Then the people of India caught the wild elephants, and tamed them, then trained them to do tricks and also useful work.

About 2250 years ago there was a famous king in Europe named Alexander, who went to India. There he and his followers saw the wonderful things that the people of India had taught the elephants to do. So they brought some of these people to Europe, with their elephants. That is how the people of Europe first learned about the wonderful habits of elephants. In our own times, wise people who bring elephants to Europe and America also bring a few men who know the habits of elephants.

That is why it is such fun to watch the elephants at a circus.[39]

Now I shall tell you how naughty elephants are punished. I have already told you that if a naughty elephant attacks any other elephant in the herd, all the other bulls surround him and keep him there, till the president of the herd comes and punishes him. Now I shall tell you how that is done.

The bull elephants stand in a ring a few yards away from the culprit; but they all face him, so that they can watch him all the time. Then the president of the herd steps into the ring, and walks toward the back of the culprit.

"But if the culprit keeps turning round, so that the president cannot get behind him?" you may ask.

Then two of the bulls forming the ring step in; and they come and dig the culprit in the ribs with their tusks, one on the right side and the other on the left side. Then the culprit cannot turn; he must stand still and take his punishment.

And this is the way the punishment is given.[40] The president gores him with his tusks on the hind quarter, just as a father spanks his naughty boy—only much harder! In fact, after two or three blows from the president's tusks, the culprit's back is very sore.

How long does this punishment last? Well, just about as long as the spanking of a naughty boy by his father. How long is that?

"Till he says he is sorry, and won't be naughty again," you may say.

That is exactly what happens to the bad elephant. The president goes on goring him till he says and shows that he won't be wicked any more. Yes, an elephant can say that he won't be wicked again by whining; and he can show it by the way he holds his head and trunk. You will understand that better from the story I shall now tell you. It is a true story. It is about a bad elephant in the service of men after the elephant had been tamed; but the punishment for being wicked would have been just the same if he had been a wild elephant in the jungle.

It happened a few years ago, when King George and Queen Mary of England went to[41] India. At that time a young reigning prince in India had just succeeded to his father's throne. So there were many ceremonies at the palace, and festivities among the people. These functions lasted a whole week, and several elephants were used in processions.

One day the elephants were taken to a place ten miles away to do useful work, such as to pile timber for building a bridge. Among these elephants was one called Mukna.

Mukna was a bad-tempered elephant. His tusks never grew more than half-size. Bull elephants whose tusks do not grow to their full size are sometimes bad-tempered; they seem to have a grudge against everybody. Such elephants are always treated with special kindness, as if to make up to them for their loss.

But in spite of all the kindness Mukna received, his temper grew worse and worse. He was punished for that, though very lightly; he was merely deprived of delicacies in his food. Elephants in the service of men usually get hay, grass, and leaves to eat; but on special days they get sugar cane, bananas, and a kind of pancake, all of which are great delicacies to an elephant.

Mukna's keeper had deprived him of these[42] delicacies for his bad temper, just as a naughty boy's father may deprive the boy of ice-cream. That should have been a lesson to Mukna to be good. But it was not. Instead, he got worse.

One morning, when all the elephants were working, Mukna's keeper ordered him to lift a log. Mukna did not obey. He merely stood still.

Now, disobedience is a serious fault in an elephant—just as it is in a child. In fact, it is the beginning of all faults on earth, as the Bible says. If people once allowed even an elephant to be disobedient, they could not control him any more—just as if a naughty boy were to be left unpunished for disobeying his parents or teacher, he would get worse, and disobey his superiors, and even the law, when he grew up.

So Mukna's keeper looked at him sternly and said, "I command you for the second time to lift that log!"

But Mukna would not yet obey. He merely stood still.

Then all the other elephants looked up from their work, just as grown-up men in a workshop look up if they hear the foreman scolding a bad workman. Those other elephants knew what an awful crime disobedience was.[43]

Then in a deep and stern voice Mukna's keeper said to him, "I command you for the third and last time to lift that log!"

But for the third time Mukna refused to obey.

"Then you shall hear about this!" the keeper said, just as if he were talking to a disobedient workman.

The keeper did not say anything more. But two of the nearest bull elephants stepped up to Mukna, one on each side of him—just like a couple of policemen arresting a criminal. Then a third bull came up in front of Mukna, and stood with his back to him, so that all three police elephants faced the same way as Mukna—as you see in the picture on page 45.

Then at the same time the three police elephants stepped backward, so that Mukna also was forced to step backward. Step by step the three police elephants went backward till Mukna's hind legs came against the trunk of a tree. There Mukna was held for a moment, so that he could not wriggle away. For the elephant in front prevented him from moving forward, and the tree prevented him from moving backward; and the two elephants on the sides prevented him from moving sideways.[44]

Then the keeper stepped to the tree and fastened one of Mukna's hind legs to the tree with a chain—so that he could not run away. The three police elephants then went back to their work.

Now I must tell you that in a herd in the jungle a bad elephant is punished at once by the president. But it is slightly different among elephants in the service of men, because there they have no elephant president, but a man president, who might be away at that time. That man is called the elephant master.

That is just what happened when Mukna was disobedient. The elephant master happened to have gone to the palace on a visit. So Mukna's keeper called a messenger and sent him to the palace to report Mukna's disobedience. The messenger had to ride on another elephant to go that distance.

Mukna saw that elephant going toward the palace with the messenger. Mukna knew why! It was to fetch the elephant master, who would punish him! Even a dog that has been naughty will cringe and whine at the sight of a whip, because it knows that its punishment is coming.

Policemen Elephants Arresting a Criminal Elephant

Policemen Elephants Arresting a Criminal Elephant

But Mukna did not cringe and whine. Instead he became defiant—just like a very bad[47] boy. He held up his head and curled his trunk tight in a spiral in front of his chest. In an elephant that is a sign that he is defiant or determined, just like a man who folds his arms tight across his chest. Mukna was unrepentant.

The messenger reached the palace and reported Mukna's disobedience; and the elephant master said that he would come that afternoon to punish Mukna.

The reigning prince said that he also would come. As he had just ascended his throne, he wanted to teach a lesson to all criminals in his domain from the beginning of his reign, and Mukna was the first to commit a crime in the prince's reign. For, I must tell you, all elephants in service in India are treated just like men; they are rewarded as good citizens or punished as criminals. So Mukna was regarded as a criminal.

The prince asked three other young princes, his cousins, to come with him. A young American was then staying in the palace as a guest, and he also was invited to come.

That afternoon the royal party went with the elephant master to the place where the elephants were; there were about thirty bulls, besides Mukna. The place was a clear space,[48] about a hundred yards across, with a lot of trees along the sides. Mukna was tied by the hind leg to one of those trees.

The royal party got out of their carriages and entered the open space on foot, quite near the spot where Mukna was tied up. They were not thinking of Mukna just at that moment, as they were talking of the grand feasts at the palace. So they did not notice Mukna at once.

Meanwhile Mukna had been brooding all day. He knew that his punishment would come very soon. "I will do it—I will do it!" he must have been saying to himself all the time. In that way he had worked himself into a fury.

When the royal party entered the open space, the young American happened to be nearest to Mukna. As he had just arrived from America, he did not know much about elephants; so the young American did not notice that Mukna was chained up to the tree by the hind leg, and that he was the bad elephant they had come to punish. Instead, the young American thought that Mukna was just one of the ordinary tame elephants working there.

So as the royal party happened to pass about[49] ten yards in front of Mukna, the young American stepped aside and said, "Hello, I must pat you!" Saying that, he raised his hand and stepped toward Mukna to pat him.

But meanwhile, when Mukna had seen the elephant master arrive with the royal party, he knew that the moment of his punishment had come! "I will do it—I will do it!" he had kept saying before. So when the young American raised his hand, Mukna suddenly made up his mind to do it now!

Mukna gave just one short trumpet. The next instant he gave a vicious tug with his hind leg—and snapped the chain! With a huge stride he came toward the American and the royal party. He would "do it" now! He would kill them all!

Nothing could stop him from doing it, it seemed. He would knock them down and trample them to death.

But meanwhile the elephant master had heard the trumpet Mukna had given a moment before he broke the chain. And in an instant the elephant master realized what would happen.

"Run for your lives!" he shouted to the young American and the four princes. And he ran himself.[50]

But an elephant can run much faster than any man. It seemed that nothing could save those six men; they would all be trampled to death. The only direction in which they could run was toward the middle of the open space—away from Mukna. Even if they reached it, they would still have to run toward the trees on the far side. Could they reach the trees in time? No! Mukna was gaining upon them. It seemed that in a few more strides Mukna would hurl himself upon them, and there was nobody to stop him.

But yes—there was!

For meanwhile, just as the elephant master had heard the trumpet Mukna had given, all the thirty bull elephants had also heard it. Most of them were too far off, near the line of trees; but there happened to be a bull a little nearer the middle of the open space. He saw at once that he could not overtake Mukna, if he merely chased him. So, how could he stop Mukna from murdering the six men?

I shall tell you. This is what that bull elephant did. As soon as the men had started running, he saw in what direction they were going. So he turned slightly, and ran also in that direction. As Mukna gained upon the men, he too came nearer and nearer to the men.

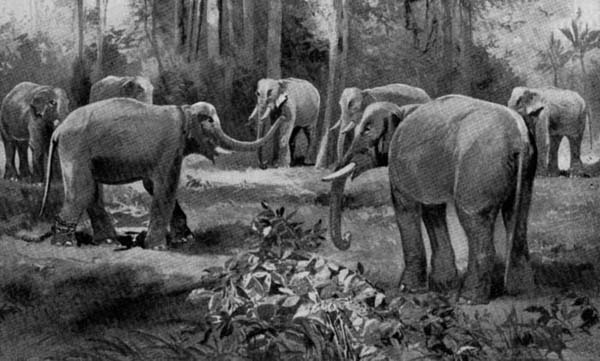

Good Elephant Heading off a

Criminal Elephant

Good Elephant Heading off a

Criminal Elephant

Mukna had come within three yards of the young American and the reigning[53] prince, who were running together. "Now I have got them!" Mukna must have thought. One more stride, and he would trample them to death!

But that instant the other bull elephant also ran close up to the two men—and hurled himself between Mukna and the two men.

Mukna's blow fell upon the bull elephant's side, and knocked him down. But Mukna tripped over him, and also fell. The two elephants rolled over and over upon the ground.

Meanwhile the young American and the reigning prince and all the other men, ran on to safety behind the trees.

When Mukna regained his feet, he realized that the men he had attempted to kill had escaped. And he also realized that now his punishment would be most terrible—first for the disobedience, then for the attempted murder. So in an instant he made up his mind to run away; he would escape to the jungle and become a wild elephant once more—even if he had to be a solitary wanderer in the jungle.

Sometimes in the wild West of America in[54] the past, men who had committed crimes would escape from the sheriff into the wilds and become outlaws. Mukna wanted to do just that. So he turned toward the trees on the side of the open space, to run away into the jungle.

But a most wonderful thing had happened. Without a word of command from anyone, all the other bull elephants had stepped to the gaps between the trees, each to the gap nearest him—as they would have done when they were wild elephants in a herd, to stop a criminal among them. And all of them were now facing Mukna.

Mukna turned to the right to find a way of escape to the jungle; but all the gaps on the right were guarded by bull elephants. Mukna turned to the left; but all the gaps on the left were guarded likewise. Mukna turned in all directions; but in all directions the gaps were guarded. He could not escape.

Then the elephant master recovered from his fright. He stepped out from behind the tree where he had hidden. For the first time he gave a command.

"March!" he cried to the elephants.

And the elephants marched toward Mukna. They came nearer and nearer, till they formed[55] a ring around Mukna near the middle of the open space. Mukna looked frantically this way and that way; but he saw a ring of elephants all round him, a dozen yards away; and the tusks of all were pointed toward him like a row of bayonets.

Then the elephant master and the royal party came and stood just outside the ring, at the back of the elephants.

There they held a trial, just as in a court of law. Mukna was accused of two crimes: first, disobedience; second, attempted murder. A man was appointed to defend him at the trial, just as in a court of law a criminal may have a lawyer to defend him.

The elephant master presided at the trial of Mukna. He was the judge.

When the trial began, Mukna's keeper first gave evidence; that is, he said that Mukna had disobeyed his order, not only once, but three times.

Then several other keepers came forward as witnesses, and gave evidence; that is, they said that they saw Mukna disobey the order.[56]

Then the man who was appointed to defend Mukna spoke for him; he was called the elephant counsel. The elephant counsel argued that Mukna must have been ill-treated to make him disobedient. So he questioned all the keepers. But all the keepers said that Mukna had not been ill-treated to make him disobedient.

"He may not have been ill-treated just that minute," the elephant counsel still argued. "But was he not ill-treated before? An elephant has a long memory; he never forgets an injury, or an act of kindness. An elephant has been known to remember both injury and kindness for more than twenty years. Then did not Mukna's keeper ever ill-treat him?"

But all the other men who were in charge of all the elephants gave evidence that Mukna's keeper had never ill-treated him; nor had anybody else ill-treated him—except that Mukna had been punished before for bad temper by being deprived of delicacies in his food. So Mukna had no true cause for disobeying the order that day.

Thus the charge of disobedience was proved against Mukna.

Then came the second crime of which Mukna was accused, namely, attempted murder. And[57] that was very quickly proved, as everybody there had just seen that crime.

So the elephant master, who was the judge, pronounced sentence of punishment on Mukna. Mukna was ordered to receive ten blows for the disobedience, and ten blows more for the attempted murder.

Now among the bull elephants forming the ring around Mukna was one who had huge tusks. So the elephant master ordered him to give Mukna the twenty blows. Of course the elephant could not count the number of blows he was to give. So the elephant master was to count for him, and tell him when to stop.

The elephant who had the huge tusks stepped into the ring, and tried to get behind Mukna, but Mukna turned around to prevent him from doing so. Then the elephant master ordered two other elephants to step into the ring. These two came and pointed their tusks at Mukna's ribs on each side. So Mukna could not turn. In defiance he held up his head, and curled his trunk tight before him.

"Hit me, if you like, but I won't give in!" he seemed to say.[58]

Five blows he took from the other elephant's tusks without flinching. But at the sixth blow he stumbled forward, and fell to the ground.

The elephant master stepped into the ring.

"Arise!" he commanded.

But Mukna would not rise.

Then the elephant master made a sign to the two bulls. They came to Mukna from each side, and prodded him in the ribs with their tusks. So Mukna was forced to stand up.

He steadied himself and received four more blows. Then at the next blow, which was the eleventh, he fell again.

"Arise!" the elephant master commanded.

Mukna again refused to arise. So the two bulls on the sides prodded him again, and forced him to arise.

This time Mukna stood only two more blows; then he fell again. The place where he was receiving the blows was now raw and bleeding. So the elephant master gave him a chance.

"Is it enough?" he asked.

But Mukna defiantly arose to his feet, without waiting to be prodded. And he defiantly held up his head and curled up his trunk.

"You may hit me as much as you like, but I won't give in!" he seemed to say.[59]

At the next blow, which was the fourteenth, Mukna again fell. He was getting weaker and weaker, and now he could not stand more than one blow at a time.

Seeing his weakness, the elephant master allowed him to lie there for five minutes.

Then he asked Mukna, "Is it now enough?"

Slowly, painfully, Mukna got up. He looked around with bleary, bloodshot eyes; he thought, "Can I not yet escape?"

But a row of tusks, like a row of bayonets, faced him on all sides.

Still he would not give in. With a fierce resolution he tried to curl up his trunk in defiance. He could not do so at once, but after an effort he succeeded.

"I won't give in, even if I die!" he seemed to say, though he was rocking unsteadily in growing weakness.

"Then we shall break your obstinate spirit!" the elephant master cried.

So Mukna received the next blow, which was the fifteenth. He fell. But after a while he rose again in defiance, and received the sixteenth blow. Then he fell in a heap. The side of his head hit the ground, and he rolled over.[60]

"Is it enough at last?" the elephant master asked. He waited.

Three times Mukna tried to raise his head in defiance, even as he lay on the ground; and three times he tried to curl up his trunk. His head went half-way up, and his trunk curled half-way. He lay on the ground just like that for a minute or two, his whole body quivering with pain and weakness.

Then perhaps the memory of all the kindnesses he had formerly received came back to his mind. Yes, an elephant never forgets an injury, but he never forgets a kindness either. Perhaps Mukna remembered at that moment all the petting he had received when he was a good elephant, all the sugar-canes and bananas and pancakes—and all the rewards for being gentle and docile and obedient. And now he realized that, instead of receiving these good things, he was receiving a most terrible punishment for being wicked, and for being obstinate in wickedness. How foolish he was!

He saw it all clearly in that moment, as he lay in shame and disgrace before all his comrades, all the other elephants. Then Mukna's head began to droop and droop; and his trunk began to unwind. The trunk hung loose and[61] limp before him; and his head sank lower and lower, till it lay humbly in the dust.

A low cry, almost like a moan, escaped his lips. It seemed to say, "I am sorry for being wicked and obstinate! I repent! Forgive me!"

Immediately the elephant master gave a sign. All the other elephants fell back. Their task was done. They returned to their usual work.

Then several of the keepers came with buckets of water, and bathed Mukna's wounds. Afterward they put on the wounds a poultice of herbs, to cure the wounds in due time.

So Mukna received only sixteen blows, instead of the twenty, because he repented of his crime.

"But if he had not repented?" you may ask.

Then he would have received the four remaining blows later on, when he was strong enough again to receive them. For the sentence of punishment must be carried out fully, like the sentence of a court of law, unless the criminal repents.

Among wild elephants in the jungle it sometimes happens that an elephant becomes so[62] wicked that he does not repent when he is being punished by the president of the herd. Then the president gives him as many blows as he can bear; that is, till he cannot rise from the ground. Then he is left there to recover by himself.

Sometimes such an elephant goes from bad to worse. For a few months his wounds may hurt him; and so he may be on his good behavior. But afterward, when the wounds have healed completely, he may commit a fresh crime. Then, of course, he is punished again. And now the place gets so sore and raw that it takes much longer to heal, and even then the place is full of scars.

If he should get unruly and commit a crime once more, would he be punished just the same? Yes, he would be. But I must tell you that a herd of elephants does not want a criminal among them. So after the third or fourth crime all the other elephants drive him out of the herd.

Then this very bad elephant meets a most awful fate. He becomes a solitary wanderer in the jungle. No other elephant will have anything to do with him. He is a rogue elephant.

"But could he not go to another part of the[63] jungle and join some other herd of elephants who don't know that he is a rogue?" you may ask.

He could. But those elephants would find out at once that he had been driven out of his own herd for being a rogue.

How would they find that out at once? By seeing the scars of the wounds on the place where he had been repeatedly punished. Those scars are the brand of the rogue elephant.

So the new herd also would drive him out, for neither do they want a rogue among them.

Thus, no matter what herd the rogue elephant tried to join, he would be driven out.

Then he would be fated to roam the jungle by himself all his life—which is a most awful punishment. An outlaw among men has a similar fate, as he is shunned by all honest people.

A rogue elephant, being the outlaw of the jungle, does not live long. Just as an outlaw among men gets shot by the sheriff's men sooner or later, so also a rogue elephant gets shot by hunters. For, although the hunters must not shoot an ordinary wild elephant[64] that is a member of a herd, they may shoot at sight a rogue elephant that is roaming in solitude.

So, my dear children, remember that such a terrible fate comes to a rogue elephant who may have begun his downward path by just one act of disobedience or some other fault—and who obstinately persisted in his wickedness, and would not repent.

On the other hand, how much wiser it is to repent, even if one has been so foolish as to do wrong! Mukna committed the most terrible crime—he actually tried to kill people; and then he tried to run away into the jungle and perhaps become a rogue elephant. But afterward, when he was being punished, he repented of his crimes. So, what happened?

I shall tell you. Mukna was put on probation for a year; that is, the keepers watched him for a year to see if he would behave well. And for the whole year Mukna was on his best behavior; he was gentle and docile and obedient, and he did whatever he was ordered to do, even the hardest work. And he did that willingly, as if to prove that he had truly repented.[65]

Then those very princes whom he had tried to kill felt sure that Mukna had begun a new life, and would always be good in the future. So the princes took him back into favor.

And today Mukna wears a cloth-of-gold, with gold rings on his tusks, and he walks in a royal procession. Sometimes he carries grand people on his back, and sometimes children. And no elephant is more gentle and thoughtful with little children than he is. For he actually curls the end of his trunk near the ground for them to sit upon—and then he lifts them up to his back, three at a time!

So far most of the animals I have described to you are vegetarians, that is, they eat vegetables of all kinds, for even leaves, herbs, and grass may be classed as vegetables. These animals are the elephant, the buffalo, the deer, the antelope, and others. The bear is the only animal I have so far described to you (in Book I) that eats both vegetables—that is, the roots of trees—and the flesh of other animals as well.

But now I shall describe to you quite a different class of animals, namely, animals that eat only meat. Among these animals the most important group is the Cat Tribe, or the felines, as they are sometimes called. They possess many of the qualities of the ordinary cat.

The principal felines are the tiger, the lion, the leopard, the puma, and the jaguar. All felines have a special kind of fangs, tongue, claws, and paws, which I shall now describe in detail.[67]

Besides the ordinary teeth, every feline has two pairs of strong fangs which look like big projecting teeth. One pair of fangs is placed on the upper jaw, pointing downward; they are wide apart. The other pair of fangs is placed in the lower jaw, pointing upward; they are not quite so far apart as the fangs of the upper jaw. Why? So that the animal can close its mouth comfortably without striking the lower fangs against the upper fangs.

These fangs are three to four inches long in a tiger or a lion; they are not quite so big in a leopard or other feline. The fangs of the tiger or the lion are so strong that he can hold down a heavy bullock by gripping it with his fangs. He can also drag the bullock along the ground by gripping it in that way, and can use the fangs to tear out a large piece of meat from the body of his prey.

When the tiger or the lion gets a piece of meat into his mouth, he uses the upper fangs to pierce the meat: that is, the meat lies on the ordinary teeth on the under jaw, and the two fangs of the upper jaw come down on the meat and cut it into two or three pieces. The tiger[68] or the lion could chew the meat a little more, with the help of his ordinary teeth, but he does not need to. Every animal of the Cat Tribe has a strong digestion; so the tiger or the lion merely cuts up the meat a few times with his fangs and then swallows it.

A feline's fangs, however, are too big to tear off small pieces of meat from a bone. So it uses its tongue to scrape off the small pieces of meat. That is the reason why a feline's tongue is very rough. So again you see, as I told you in Book I, that every animal has the gift it needs. If the feline did not have a rough tongue, it could not eat the small pieces of meat on a bone; and so a portion of its food would be wasted. No inhabitant of the jungle wastes food. It is only we who waste food.

The claws of every feline are retractile. That is, the claws can be drawn in, or sheathed, whenever the animal desires; also, the claws can be thrust out, whenever the animal desires to do that.

Why is it necessary for a feline to be able to[69] do both—to draw in its claws, and to thrust them out?

Because when the animal needs food, it must thrust out the claws to seize it. But in just running about in the jungle, it does not need to use its claws; so it draws them in. In fact, if it did not draw in its claws then, the claws would soon be worn out by rubbing against the ground. And even if the claws were growing all the time, they would be also wearing off all the time. So to keep the claws sharp for use only when the animal wants to seize something, it keeps the claws drawn in at other times.

Here I ought to tell you that a dog's claws are quite different from the claws of a feline, even from those of an ordinary cat. The cat's claws are of course retractile, as I have just described to you. But a dog's claws are rigid; that is, they are stiff and thrust out all the time. Why? Because the dog does not use its claws. It seizes its food with its mouth, not with its claws. It even defends itself with its mouth, that is, with its teeth.

But a feline uses its claws to seize its food, and even to defend itself. You may have noticed that even an ordinary cat defends itself with its claws. When a dog chases a[70] cat and corners it, the cat turns and defends itself with its claws.

Once upon a time, many, many hundred years ago, the dog did use its claws; they were then retractile. But the dog stopped using its claws; then they became rigid. The dog lost the power of drawing in its claws.

In our own bodies, if we do not use a particular gift for a long time, we lose the power of using that gift. When we are born, our left hand is just as good as our right hand. But because we do not use the left hand much in doing things, we lose the power of using it quite as well as we use the right hand. Little boys and girls should practice using the left hand. Then if by some accident the right hand is lost, they would not be quite helpless.

As for the felines, they retain the full power of their claws by constant use. So, because the claws are very useful, every feline takes care of its claws,—especially the tiger. Why, the tiger cleans his claws every day! In the jungle there are many trees that have a soft bark. So the tiger goes to one of these trees every day, and digs his claws into the bark. Then he draws his claws sideways along the bark, and that cleans out the claws. The[71] tigress also cleans her claws every day in the same manner.

Some little boys and girls do not clean their nails every day. Then sometimes a piece of dirt gets in under a nail and causes a sore. But the tiger and tigress are wiser. If part of a piece of meat that they have torn up were to remain under a claw, it would fester and cause a sore. So the tiger and tigress clean their claws every day.

The paws of every feline have also a special quality. The under part of each paw is thickly padded with powerful muscles. That gives the feline three advantages.

First advantage: it enables the feline to stalk its prey. That is, the feline can creep up to its prey quite silently. As its paws are padded, they make no sound on the ground—just as your footfall makes no sound when you wear rubbers over your shoes.

Second advantage: the padded paw enables the feline to strike down its prey with a severe blow. When it wants to strike down its prey, the feline hardens the muscles under its paw; the blow of its paw is then something like that[72] of a hammer. A tiger has often been known to smash the skull of a buffalo with a single blow of its paw.

Third advantage: the padded paws enable a feline to leap farther. After a feline has crept up as near to its prey as it can, it has still to leap upon its prey to seize it. Then the muscles under the paws act like springs, and enable the feline to give a big leap. Even in running, the muscles act somewhat like springs. You must have noticed that, in running, a dog gallops, but a cat bounds. That is, the dog moves its legs very quickly, but each space of ground it covers is not very long. A cat moves its legs not quite so quickly, but the space of ground it covers at each bound is much longer. The cat and all felines can give a bigger bound because of the muscles under their paws.

Having told you all the qualities common to animals of the Cat Tribe, I shall now describe some of these animals in detail.

The tiger lives in most of the countries along the south coast of Asia, that is, all the way from Persia to China. Some tigers are also found in the northern countries of Asia, such as Siberia; but there are very few of them there. And, of course, these few tigers in the cold northern countries of Asia are a little different from those in the hot southern countries. For the tigers in the cold countries have thick fur on their skin, and a layer of fat under their skin—just to keep them warm. So they are too fat to be as muscular and active as the slim and lithe tigers that live in the hot countries in the south of Asia.

Now please remember one thing more about the dwelling place of the tiger: there is no tiger in Africa. Even clever people do not always know that. When ex-President Roosevelt went on a hunting trip to Africa a few years ago, he shot many wild and ferocious animals there, and some newspapers said that he had shot several tigers.[74]

That was a mistake. The animals that he shot were leopards, not tigers. You can at once tell the difference between a leopard and a tiger: a leopard is spotted, but a tiger is striped. I shall tell you all about that presently.

Even as regards the habits and character of the tiger, people often make mistakes. There is no animal that has been so much abused as the tiger. Most people call the tiger a "cruel" and "bloodthirsty" animal.

But that is not true. By "bloodthirsty" people usually mean that the tiger kills his prey for the mere sake of killing, and that he kills more animals than he can eat, just for the mere fun of killing.

That is not true. A tiger is not really "bloodthirsty" in that way, as I shall explain to you presently. A tiger never kills for the mere fun of killing. Some men and some naughty boys do that! They think it great sport to kill harmless wild animals, which they cannot possibly eat or use in any way; and some naughty boys kill frogs and lizards and other small animals, just for the mere "fun" of killing, as they call it.

Tiger

Tiger

A tiger never does that—and he is supposed[77] to be the worst animal of all! For one thing, a tiger is not such a fool as to kill his prey for the mere sake of killing. Men formerly ate the flesh of the American bison, or buffalo, as it was generally called. But then they killed off whole herds of these buffaloes. So now there are no more buffaloes left for food in those places. A tiger is wiser. He does not destroy his own food supply needlessly.

People are also wrong when they say that a tiger is "cruel," and that he tortures his prey before killing it outright. That is not true of the tiger. In fact, hardly any animal is needlessly cruel, as some men and naughty boys are—for instance, naughty boys who torture frogs and lizards and then kill them.

It is true that a tigress does worry her prey before killing it. But why does she do so? Simply to teach her cubs how to catch and kill the prey, so as to provide food for themselves when they grow up. I shall explain that fully presently. So please remember this once for all: hardly any animal is needlessly cruel or bloodthirsty.

"But a cat does worry a mouse, before killing it," you may object. "Is not that needless cruelty?"[78]

That seems quite true. But there is a reason for it: the cat first began to do that to teach her kittens how to catch mice, when she was a wild animal in the fields. Once upon a time the cat was a wild animal, but now people have tamed it into a domestic animal. So the cat still retains some of its wild habits.

But you will understand all that when I tell you more fully about the tiger, which is the largest and strongest animal of the Cat Tribe.

I shall describe to you the actual life of a tiger family in the jungle. A tiger family consists of the father, the mother, and from two to four cubs. Three is the usual number of children that a tiger and tigress have.

When the cubs are only a few days old, they are quite helpless. So the mother stays with them in the den, while the father goes in search of food. The den is usually a hollow under a large tree.

If the father tiger catches a prey which he can carry, such as a deer, he brings it home with him. Then he and the tigress eat it together.

But if the prey is too large to carry, such as a bullock or a buffalo? Then the tiger first eats[79] a good portion right after catching it. Then he comes home to the den and sends out the tigress to eat her share, while he stays home in the den and takes care of the cubs.

But here is something for you to think of. In sending the tigress out to eat her share of the prey, the tiger must tell her where the prey is lying; otherwise she might go the wrong way. Why? Because the prey might be lying a mile or more from the den, so that she could not possibly trace it merely by its scent. And the prey might have been caught in any direction, especially if the tiger had to chase it or stalk it for a long distance. So nobody could tell beforehand in what direction a tiger might catch its prey.

The tigress could not merely follow the tiger's paw marks to get to the prey, as the tiger may have gone out several times that day or the day before; and so there would be several lines of paw marks, and she would have to search very long by following all the paw marks in turn. Yet she always takes the right direction, and gets to the prey quickly. Hunters in the jungle have found that out. How does she do it?

The only way to explain it is this—the tiger[80] tells her where the prey has been caught and is now lying. That is what hunters believe from the actual facts they have observed. Then that shows that animals have a method of communicating with one another. Of course they do not use our words. They must have words or sounds, or even signs, of their own.

Now I shall go on with the tiger family. The cubs, of course, drink their mother's milk. They do that till they are three months old.

But meanwhile, when they are six weeks old, they can walk and trot. They are then very playful, and they leap and gambol and tumble over one another.

They are then able to go about with their father and mother for a short distance. So if food gets scarce for the tiger and tigress, they leave their old den altogether, and go to live elsewhere in the jungle where food may be more plentiful.

In this house-moving the cubs can trot behind their father and mother for a mile or two. Then, for fear of tiring the cubs, the tiger and tigress scoop a hollow under a tree, and place them there. The tiger and tigress go on ahead till they find the new home. Then they come back to fetch the cubs.[81]

If the cubs are now two months old, the father and mother need have no fear in leaving them for a few hours. So in their new home the tigress may go hunting with the tiger every day.